1.

Here’s a fact I find hilarious: we only know about several early Christian heresies because we have records of people complaining about them.1 The original heretics’ writings, if they ever existed, have been lost.

I think about this whenever I am about to commit my complaints to text. Am I vanquishing my enemies’ ideas, or am I merely encasing them in amber, preserving them for eternity?

2.

The poet Paul Valéry said that, for every poem you write, God gives you one line, and you supply the rest.2 Amy Lowell, another poet, described those in-between lines, the ones you provide, as “putty”. You get no credit for God’s lines; all artistry is in the puttying.

3.

In the long run, every writer is misunderstood.

Apparently Sir Arthur Conan Doyle considered his Sherlock Holmes stories “a lower stratum of literary achievement” and thought his novels were far better. (Can you name any?) Borges once remarked, “I think of myself as a poet, though none of my friends do.” (Didn’t even know he wrote poems.) Sylvia Plath derided The Bell Jar as “a pot boiler”. (That is, a piece of art produced to keep the heat on.) Elizabeth Barrett Browne wrote poems about slavery and politics, but now the only poem anyone remembers is the one about how much she loves her husband (You know it: “How do I love thee? Let me count the ways”). After he published The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, Thomas Kuhn spent the rest of his life arguing with his critics (and—purportedly—throwing ashtrays at them).

4.

I remember a young man in Paris after the war—you have never heard of this young man—and we all liked his first book very much and he liked it too, and one day he said to me, “This book will make literary history,” and I told him: “It will make some part of literary history, perhaps, but only if you go on making a new part every day and grow with the history you are making until you become part of it yourself.” But this young man never wrote another book and now he sits in Paris and searches sadly for the mention of his name in indexes.

5.

The Wadsworth Constant says that you can safely skip the first 30% of anything you see online. (It was meant for YouTube videos, but it applies just as well to writing). This is one of those annoying pieces of advice that remains applicable even after you know it. Somehow, whenever I finish a draft, my first few paragraphs almost always contain ideas that were necessary for writing the rest of the piece, but that aren’t necessary for understanding it. It’s like I’m giving someone a tour of my hometown and I start by showing them all the dead ends.

Anyway, this reminds me of my favorite windup of all time:

6.

The internet is full of smart people writing beautiful prose about how bad everything is, how it all sucks, how it’s embarrassing to like anything, how anything that appears good is, in fact, secretly bad. I find this confusing and tragic, like watching Olympic high-jumpers catapult themselves into a pit of tarantulas.

7.

All emotions are useful for writing except for bitterness.

Good writing requires the consideration of other minds—after all, words only mean something when another mind decodes them. But bitterness can consider only itself. It demands sympathy but refuses to return it, sucks up oxygen and produces only carbon dioxide. It’s like sadness, but stuck eternally at a table for one.

Other emotions—anger, fear, contentment—are deep enough to snorkel in, and if you keep swimming around in them, you’ll find all sorts of bizarre creatures that dwell in the depths and demand description. Bitterness, on the other hand, is three inches of brackish water. Nothing lives in it. You can stand in it and see the bottom.

8.

All writing about despair is ultimately insincere. Putting fingers to keys or pen to paper is secretly an act of hope, however faint—hope that someone will read your words, hope that someone will understand. Someone who truly feels despair wouldn’t bother to tell anyone about it because they wouldn’t expect it to do anything. All text produced in despair, then, is ultimately subtext. It shouts “All is lost!” but it whispers “Please find me.”

9.

Or, as the writer D.H. Lawrence put it when he got into painting:

A picture has delight in it, or it isn’t a picture. [...] No artist, even the gloomiest, ever painted a picture without the curious delight in image-making.

10.

So why do writers whine so much about writing? They’re always saying things like: “I hate to write, but I love having written,” or “Being a writer is like having homework every night for the rest of your life” or “There is nothing to writing. All you do is sit down at a typewriter and bleed.” In fact, it’s nearly impossible to trace those quotes back to their original source because apparently every writer who ever lived said something similar.

Maybe it’s because writing is inherently lonely, or maybe it’s because the only people who would try to make a living from writing are messed up in the head.

Personally, I think the reason is far more sinister: making art is painful because it forces the mind to do something it’s not meant to do. If you really want to get that sentence right, if you want that perfect brush stroke or that exquisite shot, then you have to squeeze your neurons until they scream. That level of precision is simply unnatural.

11.

Maybe that’s why so few people write, and why a few people feel compelled to write. Every kind of pain is aversive to most humans, but addictive to a handful of them. Writers are addicted to the particular kind of pain you feel when you’re at a loss for words, and to the relief that comes from finding them.

I mean, here’s Ray Bradbury, sounding like a dope fiend:

If I let a day go by without writing, I grow uneasy. Two days and I am in a tremor. Three and I suspect lunacy. Four and I might as well be a hog suffering the flux in a wallow. An hour’s writing is tonic.3

12.

Remember the adrenochrome conspiracy? It claimed that children produce a kind of magical hormone when under duress, and celebrities stay forever young by feeding upon it. This is false, of course. But what if this actually describes our relationship to artists? What if we all stay alive by feeding on the products of their suffering? What if a great piece of art is like a pearl: an irritant covered in a million attempts to make it go away?

13.

I used to think that the phrase “Love the questions” was from the same pablum factory that produced “Live, laugh, love”—like, there must have been a global glut of throw pillows a few years ago, and someone figured out that you can sell them to Bed, Bath, and Beyond if you embroider them with fake-deep claptrap. Then I found out that “Love the questions” comes from a letter that the poet Rainer Maria Rilke wrote to a kid named Franz Xavier Kappus, who was trying to decide whether to become a writer or a soldier in the Austro-Hungarian army. In context, the quote is far less cringe:

You are so young, so much before all beginning, and I would like to beg you, dear Sir, as well as I can, to have patience with everything unresolved in your heart and to try to love the questions themselves as if they were locked rooms or books written in a very foreign language.

It’s even less cringe when you read the whole letter, and realize that a few sentences later Rilke appears to be counseling the poor Kappus on what to do about his excessive horniness:

Sex is difficult; yes. But those tasks that have been entrusted to us are difficult; almost everything serious is difficult; and everything is serious. If you just recognize this and manage [...] to achieve a wholly individual relation to sex (one that is not influenced by convention and custom), then you will no longer have to be afraid of losing yourself and becoming unworthy of your dearest possession.4

14.

Here’s my point. Some people think that writing is merely the process of picking the right words and putting them in the right order, like stringing beads onto a necklace. But the power of those words, if there is any, doesn’t live inside the words themselves. On its own, “Love the questions” is nearly meaningless. Those words only come alive when they’re embedded in this rambling letter from a famous poet to a scared kid, a kid who is choosing between a life where he writes poems and a life where he shoots a machine gun at Bosnian rebels. The beauty ain’t in the necklace. It’s in the neck.

15.

Maybe that’s my problem with AI-generated prose: it’s all necklace, no neck.

16.

I worked in the Writing Center in college, and whenever a student came in with an essay, we were supposed to make sure it had two things: an argument (“thesis”) and a reason to make that argument (“motive”). Everybody understood what a “thesis” is, whether or not they actually had one. But nobody understood “motive”. If I asked a student why they wrote the essay in front of them, they’d look at me funny. “Because I had to,” they’d say.

Most writing is bad because it’s missing a motive. It feels dead because it hasn’t found its reason to live. You can’t accomplish a goal without having one in the first place—writing without a motive is like declaring war on no one in particular.

17.

This is why it’s very difficult to teach people how to write, because first you have to teach them how to care. Or, really, you have to show them how to channel their caring, because they already care a lot, but they don’t know how to turn that into words, or they don’t see why they should.

Instead, we rob students of their reason for writing by giving it to them. “Write 500 words about the causes of the Civil War, because I said so.” It’s like forcing someone to do a bunch of jumping jacks in the hopes that they’ll develop an intrinsic desire to do more jumping jacks. But that’s not what will happen. They’ll simply learn that jumping jacks are a punishment, and they’ll try to avoid them in the future.

18.

Usually, we try to teach motive by asking: “Why should I, the reader, care about this?”

This is reasonable advice, but it’s also wrong. You, the writer, don’t know me. You don’t have a clue what I care about. The only reasons you can give me are the reasons you could give to literally anyone. “This issue is important because understanding it could increase pleasure and reduce pain.” Uh huh, cool!

What I really want to know is: why do you care? You could have spent your time knitting a pair of mittens or petting your cat or eating a whole tube of Pringles. Why did you do this instead? What kind of sicko closes the YouTube tab and types 10,000 words into a Google doc? What’s wrong with you? If you show me that—implicitly, explicitly, I don’t care—I might just close my own YouTube tab and read what you wrote.

19.

There’s a scene in the movie Her where Joaquin Phoenix realizes that the AI he’s fallen in love with has, in fact, fallen in love with hundreds of other people as well. The AI doesn’t think this is a big deal, but Mr. Phoenix does, as any human would, because we only know how to value things that are scarce. If love doesn’t cost you anything, is it even really love?

The same dynamics are at play in writing, even if we don’t think about them. Imagine how amazing it must have felt to receive a letter from Rilke, to know that a famous poet decided to spend his time writing those words to you, and only you. A mimeographed, boilerplate response wouldn’t have been nearly as potent: “Thanks for writing! I’m afraid I don’t have to time to respond personally to every letter, but just remember, love the questions!”).

Most writing, of course, isn’t exclusive in terms of access, but in terms of time. There’s something special about every word written by a human because they chose to do this thing instead of anything else. Something moved them, irked them, inspired them, possessed them, and then electricity shot everywhere in their brain and then—crucially—they laid fingers on keys and put that electricity inside the computer. Writing is a costly signal of caring about something. Good writing, in fact, might be a sign of pathological caring.

20.

Maybe that’s my problem with AI-generated prose: it doesn’t mean anything because it didn’t cost the computer anything. When a human produces words, it signifies something. When a computer produces words, it only signifies the content of its training corpus and the tuning of its parameters. It has no context—or, really, it has infinite context, because the context for its outputs is every word ever written.

When you learn something about a writer, say, that Rousseau abandoned all of his children, it inflects the way you understand their writing. But even that isn’t quite the right example—it’s not about filling in the biographical details, it’s about realizing that the thing you’re reading comes from somewhere. Good writing is thick with that coming-from-ness.

21.

Lots of people worry that AI will replace human writers. But I know something the computer doesn’t know, which is what it feels like inside my head. There is no text, no .jpg, no .csv that contains this information, because it is ineffable. My job is to carve off a sliver of the ineffable, and to eff it.

(William Wordsworth referred to this as “widening the sphere of human sensibility, for the delight, honor, and benefit of human nature [...] the introduction of a new element into the intellectual universe.”)

If I succeed, of course, the computer will come to know more and more of my secrets. It’s like I am slowly speaking my password aloud, and eventually the computer might be able to guess the characters that still remain, at which point it will breach all my systems and kill me. My only hope is that my password contains infinite characters, that the remaining dots keep changing their identities, so that no machine, no matter how powerful, can ever guess the rest.

We’ll see if I’m right!

22.

I probably sound like one of those guys who is always like, “AI will never do this, or I’ll eat my hat!!” and then he has to get his stomach pumped because it’s full of hats. I’m not actually interested in fighting a rear-guard action against the machines, because it’s inherently depressing. We’ve already lost a lot of ground, and we’re going to lose more.

If you take that perspective, though, you miss the point. We’ve got a once-in-the-history-of-our-species opportunity here. It used to be that our only competitors were made of carbon. Now some of our competitors are made out of silicon. New competition should make us better at competing—this is our chance to be more thoughtful about writing than we’ve ever been before. No system can optimize for everything, so what are our minds optimized for, and how can I double down on that? How can I go even deeper into the territory where the machines fear to tread, territories that I only notice because they’re treacherous for machines?

23.

Most of the students who came into the Writing Center thought the problem with their essay was located somewhere between their forehead and the paper in front of them. That is, they assumed their thinking was fine, but they were stuck on this last, annoying, arbitrary step where they have to find the right words for the contents of their minds.

But the problem was actually located between their ears. Their thoughts were not clear enough yet, and that’s why they refused to be shoehorned into words.

Which is to say: lots of people think they need to get better at writing, but nobody thinks they need to get better at thinking, and this is why they don’t get better at writing.

24.

The more you think, the closer you get to the place where the most interesting writing happens: that tiny slip of land between “THINGS THAT ARE OBVIOUS” and “THINGS THAT ARE OBVIOUSLY WRONG”. Kinda like this:

25.

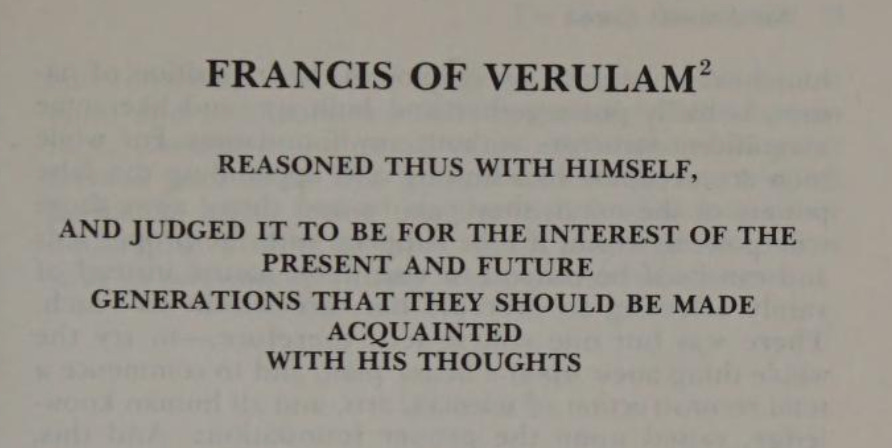

For example, after Virginia Woolf finished the first part of To the Lighthouse, she jotted in her diary, “Is it nonsense? Is it brilliance?” In his own diary, John Steinbeck wrote: “Sometimes I seem to do a good little piece of work, but when it is done it slides into mediocrity.” (That work was The Grapes of Wrath.) Francis Bacon, the father of modern science, begins The Great Instauration by wondering whether he’s got a banger or a dud on his hands: “The matter at issue is either nothing, or a thing so great that it may well be content with its own merit, without seeking other recompense.” The first page of the book does make it clear, though, which way Bacon ultimately came down on that question:

26.

I know some very great writers, writers you love who write beautifully and have made a great deal of money, and not one of them sits down routinely feeling wildly enthusiastic and confident. Not one of them writes elegant first drafts. All right, one of them does, but we do not like her very much. We do not think that she has a rich inner life or that God likes her or can even stand her.

27.

I see tons of essays called something like “On X” or “In Praise of Y” or “Meditations on Z,” and I always assume they’re under-baked. That’s a topic, not a take.

28.

Of course, that includes any post called “Notes on” something, like this very post you’re reading right now. Every writer, whether they know it or not, is subtweeting themselves. Whenever they rail against something, they are first and foremost railing against their own temptation to do that thing. To understand any author, picture them delivering their prose to a mirror.

That’s true for me, anyway. Wait, does no else do this?

See: Marcionism, Montanism

Valéry was nominated for the Nobel Prize 27 times in 12 different years and never won, so maybe God was trying to make it up to him.

This is from Bradbury’s Zen in the Art of Writing. Here’s the poet Brewster Ghiselin saying the same thing:

Poets speak of the necessity of writing poetry rather than of a liking for doing it. It is a spiritual compulsion, a straining of the mind to attain heights surrounded by abysses and it cannot be entirely happy, for in the most important sense, the only reward worth having is absolutely denied: for, however confident a poet may be, he is never quite sure that all his energy is not misdirected nor that what he is writing is great poetry.

From the translation I’m not sure if Rilke is talking about sex as in “doing the deed” or sex as in “being a man” but I choose the more interesting interpretation

"My job is to carve off a sliver of the ineffable, and to eff it."

This was fun to read on the morning of my 28th birthday 🥳