A couple years ago, I got a job interview at a big-name university and I had to decide whether to go undercover or not. On paper, I looked like a normal candidate. But on the internet, I was saying all sorts of wacko things, like how it’s cool to ditch scientific journals and just publish your papers as blog posts instead.

If the university wanted to hire me, I was pretty sure they wanted the normal me, not the wacko me. But I was also starting to suspect the wacko me was the real me. This was a big problem, because that job came with a paycheck, an office, and the approval of my peers. Could I maybe Trojan Horse myself into their department and only reveal my true nature after we’d signed all the documents (“Ha ha, you fools! Couldn’t you tell I’ve gone bananas??”)? Or could I maybe lock up my wackiness, maybe forever, or at least until I had tenure, when I could let it loose again?

Those lies were extremely tempting, but they were also lies. I knew that if I went undercover, at some point they were going to show me a picture of my wacko self and ask, “Do you know this man?” and I would have to say, “Never heard of him.” As much as I love having health insurance, I couldn’t bring myself to do that.

So in the end I went as the real me, a normal guy who was in the process of becoming a wacko, like a caterpillar who had snuggled up inside his cocoon and was soon to emerge as a, I dunno, a teeny tiny walrus in a fedora. I gave my normal talk about my dissertation—a project I loved and was happy to present—but I ended by saying, “I don’t think we need a hundred more papers like this one. We need to turn psychology into a paradigmatic science, and I think I can help do that.” I told them why I thought psychology hadn’t made much progress in the past few decades, and how it could, and how I might be wrong about everything, but I would hopefully be wrong in a useful way. When people asked me if I planned to publish my papers in journals, I said no, and I explained why.

It probably doesn’t sound like much, but this was the scariest thing I’ve ever done. This is the academic equivalent of getting on stage and mooning the audience. You’re not supposed to say this stuff, especially not at a job interview. You’re risking a fate worse than death—people might think you’re weird.

That’s how it felt when I decided to do all that, anyway. But on the actual day, I didn’t feel afraid at all. I felt free. Invincible, even. I had already condemned myself to death, so what could they do to me now? In the unlikely event that they liked the real me, great! And if they didn’t, well, better to find that out sooner rather than later. The only real danger was if they hired the fake me and then I had to pretend to be the fake me for the rest of my life.

I expected to last like 15 minutes before someone said, “Oh wow we’ve made a terrible mistake, please leave.” Instead, people were nice. Some of them were excited—if nothing else, they had never seen someone get on stage and drop their drawers before. A couple people were like “Between you and me, I like what you’re doing, but I don’t know about the others.” I never encountered those supposed others, but maybe they waited until I left their office to bust out laughing. Some were skeptical, but in a “I’m taking you seriously” kind of way. And some people didn’t react at all, as if I was being so weird that they couldn’t even perceive it, like I was up there slapping my bare buttcheeks and they were like, “Um yeah I had a question about slide four?”

And then...I got the job!!

Haha no just kidding I didn’t get the job, are you nuts?

But fortunately it didn’t hurt at all, it actually felt great!

Haha no it sucked! Of course it hurts when people hang out with you all day and then decide they don’t ever want to hang out with you again. I might be a wacko, but I’m not a psychopath.

And yet the hurt was only skin deep. It felt like I got a paper cut when I expected to be sawn in half. I guess I imagined that being myself would make me feel saintly but grim, like one of those martyrs in a Renaissance painting who has a halo around his head and a sword through his belly. Kinda like this:

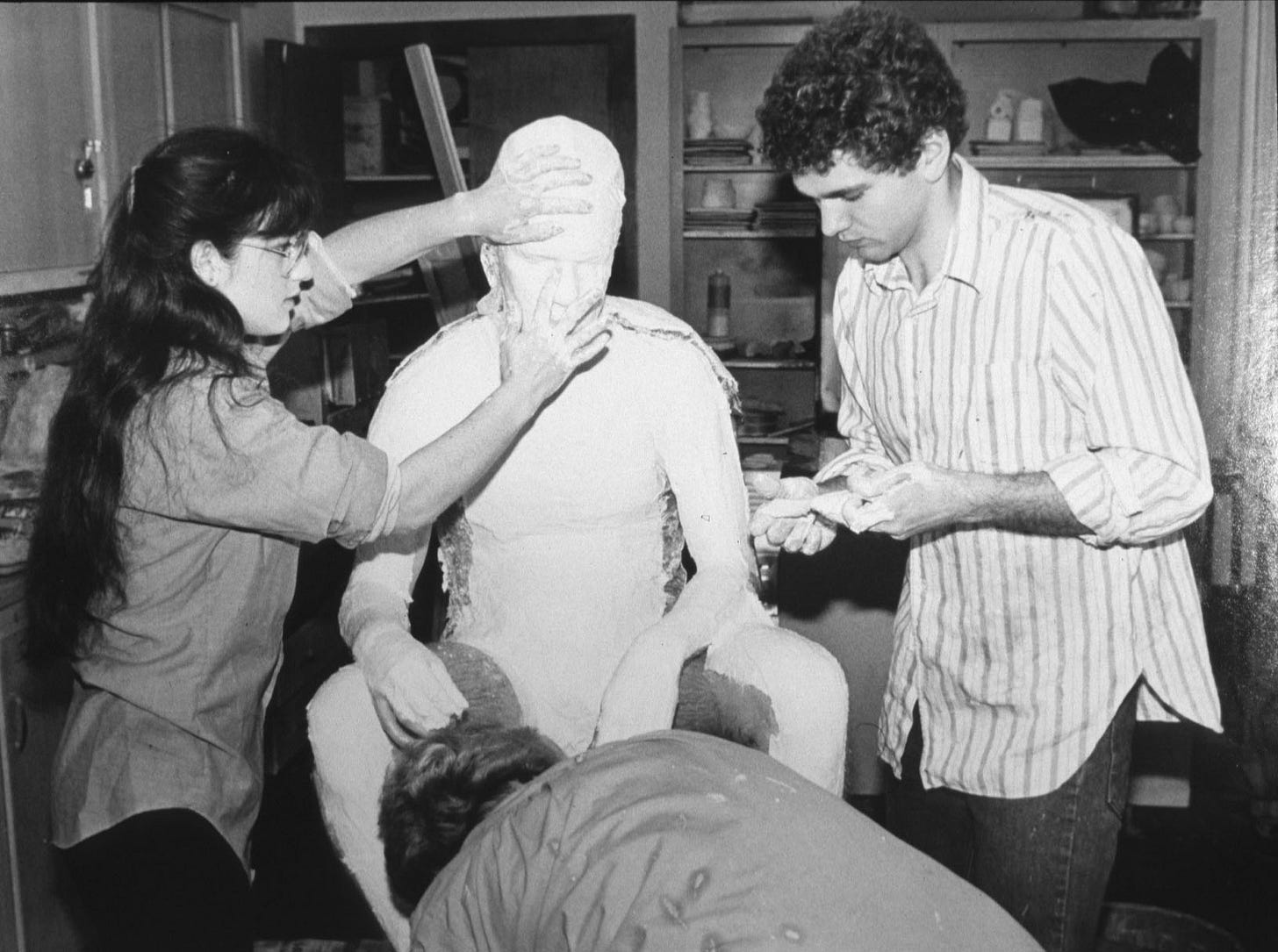

Instead, it made me feel like this:

LOOK AT THESE DUMMIES SPENDING MULTIPLE DAYS PROCESSING CASSAVA

This felt like a triumph, but it also felt confusing and silly. Why was it so hard to be myself in front of my potential employer? Why was I even considering trying to bamboozle my way into a job that I wasn’t even sure I wanted?

Maybe it’s because, historically, doing your own thing and incurring the disapproval of others has been dangerous and stupid. Bucking the trend should make you feel crazy, because it often is crazy. Humans survived the ice age, the Black Plague, two world wars, and the Tide Pod Challenge. 99% of all species that ever lived are now extinct, but we’re still standing. Clearly we’re doing something right, and so it behooves you to look around and do exactly what everybody else is doing, even when it feels wrong. That’s how we’ve made it this far, and you’re unlikely to do better by deriving all your decisions from first principles.

Here’s an example1. Cassava is tasty, nutritious, and easy to grow, but it is also unfortunately full of cyanide. Thousands of years ago, humans developed a lengthy process that renders the root edible, which involves scraping, grating, washing, boiling, waiting, and baking. It’s a huge pain in the ass and it takes several days, but if you skip any of the steps, you get poisoned and maybe die. Of course, the generations of humans who came up with these techniques had no idea why they worked, and once they perfected the process, the subsequent generations would also have no idea why they were necessary.

The knowledge of cassava processing only survived—and indeed, humans themselves only survived—because of conformity, tradition, and superstition. The mavericks who were like, “You guys are dummies, I’m gonna eat my cassava right away” all perished from the Earth. The people who passed their genes down to us were the ones who were like, “Yes of course I’ll do a bunch of pointless and annoying tasks just because the elders say so and it’s what we’ve always done.” We are the sons and daughters of sheeple.

No wonder it’s hard to be yourself, even long after we’ve gotten all the cyanide out of our cassava. Looking normal, pleasing others, squelching your internal sense of self and surrendering to the standards of your society—that all feels like a matter of life and death because, until recently, it was.2

It’s funny that none of this dawned on me even though I’ve been staring at this fact for years. My home field, social psychology, got famous for demonstrating all the ways that people will conform to the norm: the Milgram shock experiments, the Asch line studies, the smoke filled room study, the (now discredited) Stanford Prison Experiment, etc. Come to our classes and we’ll show you a hilarious Candid Camera clip where they send stooges to face the wrong way in the elevator, and the hapless civilians around them cave to peer pressure and end up facing the same way, too3:

“Ha ha! Look at what those dopes will do!” I thought to myself, profoundly missing the point. I didn’t realize at the time that demonstrating people’s willingness to conform is like demonstrating their willingness to doggy paddle when they get tossed in a lake—that’s what a lifesaving instinct looks like.

YOU MUST BE NUTS

I guess what I’m saying is: everybody tells you to be yourself, but nobody tells you it’ll make you feel insane.

Maybe there are some lucky folks out there who are living Lowest Common Denominators, whose desires just magically line up with everything that is popular and socially acceptable, who would be happy living a life that could be approved by committee. But almost everyone is at least a little bit weird, and most people are very weird. If you’ve got even an ounce of strange inside you, at some point the right decision for you is not going to be the sensible one. You’re going to have to do something inadvisable, something alienating and illegible, something that makes your friends snicker and your mom complain. There will be a decision tucked behind glass that’s marked “ARE YOU SURE YOU WANT TO DO THIS?”, and you’ll have to shatter it with your elbow and reach through.

You shouldn’t do that thing on a whim—the snickers and complaints are often right, and evolution put the glass there for a reason. Nor should you do it in the hopes that it’ll make your life easier, because on the whole, it won’t. Sticking to the paved path puts you beyond reproach. If you, say, hit a pot hole and go flipping into oncoming traffic, well, hey, that’s not on you. Go off-road, though, and you’re vulnerable to criticism. If you crash, it’s your fault. Why couldn’t you just drive on the street like a normal person?

When you make that crazy choice, things get easier in exactly one way: you don’t have to lie anymore. You can stop doing an impression of a more palatable person who was born without any inconvenient desires. Whatever you fear will happen when you drop the act, some of it won’t ultimately happen, but some will. And it’ll hurt. But for me, anyway, it didn’t hurt in the stupid, meaningless way that I was used to. It hurt in a different way, like “ow!...that’s all you got?” It felt crazy until I did it, and then it felt crazy to have waited so long.

Which is to say: once you moon the audience, you don’t have to worry anymore, because the worst is already over. All that’s left is to live the rest of your life in a world where people have seen your bare butt. And I can tell you, it’s better than you might expect.

This example comes from Joe Henrich’s The Secret of Our Success, pg. 97-99.

Our instinct to conform is so strong that it can even reprogram our taste buds. Once, at a party, some of my friends handed me a glass of wine and were like “Here, try this!” and the way they said it made me think there was something wrong with the wine, like it had gone off or something, and they wanted me to see how bad it was. (These are the kind of people I hang out with.) So I took a sip and went, “Oh, that’s rancid!”

My friends got quiet. One of them looked especially horrified. “That’s my favorite wine,” she said. She had brought it to share with everybody.

I took another sip and tried to backpedal, “Actually it’s not so bad! It’s good, even!” I said, looking insane. “I’m bad at tasting things,” I added, helplessly. (I didn’t yet have documented scientific evidence that I have a poor sense of smell and taste.) I wasn’t lying—it really had tasted bad at first, and as soon as I knew it was supposed to taste good, it did.

Whoever uploaded this clip called it “Groupthink” but that’s…a different thing

Your description of cassava processing brings to mind this quote from the novel “Courtship Rite”, by Donald Kingsbury:

Tradition is a set of solutions for which we have forgotten the problems. Throw away the solution, and you get the problem back.

I love the cassava anecdote. When to respect traditional knowledge, and when to challenge it, is a tough problem with no universal answer. I suspect society benefits most when there are some people doing both of those things.