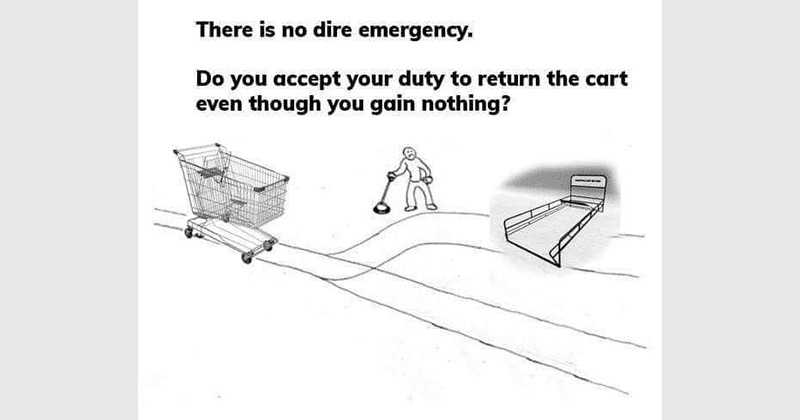

I got a bone to pick with an ancient meme. Remember five years ago, when a viral post was claiming that you could judge someone’s capacity for “self-governing” by observing their behavior in the grocery store parking lot? Good people return their shopping carts, the theory went, and bad people don’t.

Like everything that comes out of the website 4Chan, the Shopping Cart Test was designed to get people’s attention and then make their lives worse. These are the people who brought us Pizzagate, QAnon, Pedobear, the bikini bridge, and a high-profile heist of a flag owned by the actor Shia Lebeouf.1 So this meme, too, did exactly what it was supposed to do: it made people look and then it made them mad. The inevitable backlash came, the backlash to the backlash, the New York Times article, etc. People got bitter, then they got bored, then they moved on.

But not me. I think the 4channers accidentally discovered something useful. They’re right about one big thing: our moral mettle will be tested by dilemmas so small that they’re nearly imperceptible. As fun as it is to toss around Trolley Problems and Lifeboat Ethics, most of us will never actually have to decide whether to kill one to save five, or whether to toss a toddler into the sea to keep the boat afloat. You cannot purchase an experience machine, nor can you move to Omelas. But you will have to decide whether to take 30 seconds to push a cart 50 feet. If there really is a Saint Peter waiting for us at the pearly gates with a karmic dossier, it will be stuffed not with a few grand actions, but a million mundanities like this one.

Because they’re trying to turn the whole world into a kingdom of trolls, however, the originators of the Shopping Cart Test made it nefarious instead of useful by pointing it in the wrong direction. The test is presented as a cudgel to use against your fellow citizens, a way to judge them worthy of coexistence or condemnation. (In the meme’s own words, anyone who fails the test is “no better than an animal.”) But Saint Peter is not like a district attorney, willing to let you walk into heaven in exchange for kompromat on your accomplices. (“I saw Bill from down the block leave a cart in the handicapped parking spot! Do I get to have eternal life now?”) No, the point of the Shopping Cart Test is not to administer it, but to pass it—to practice a tiny way of being good, because most ways of being good are, in fact, tiny.

There should be many more Shopping Cart Tests, then, and we should be pointing them at ourselves, rather than at each other. So I’ve been keeping track of them—those almost invisible moments when you can choose to do a bit of good or a bit of bad. I think of these as keyholes to the soul, ways of peeking into your innermost self, so you can make sure you like what you see in there. Here are seven of ‘em.

1. THE BLUETOOTH TEST

God help the driver who gives me control over the music in the car, because the second I get that Bluetooth connection, I become a madman. I take ‘em on a wild ride through my Spotify, hellbent on showing them just how interesting of a guy I am, and how cool and eclectic my tastes are. “They’re playing authentic medieval instruments,” I shout over the music, “But it’s also mixed with death metal!”

I was once on a third date where we needed to drive somewhere, and when my date connected to the car’s Bluetooth, I figured she would do like I do and show off her discography. Instead, my favorite tunes started coming out of the speakers. “Whoa, you like this too??” I asked. “No,” she said, “I’m playing it because you like it.”

I was awestruck and dumbstruck. I had never even entertained the idea of creating a good experience for someone else. And I had never realized that the only pleasure greater than playing the music you love is other people playing the music you love. The scales fell from my eyes as I thought of all the times I had been in charge and decided, without thinking, to cater to my own tastes: order the food I like, set the temperature to what’s comfortable for me, pack the itinerary full of stuff I want to do. I’ve come to think of this as the Bluetooth Test: when you’re given the smallest amount of power, do you use it to make things nice for everybody, or just yourself?

Anyway, me ‘n’ that girl are married now.

2. THE CIRCLE OF HELL TEST

You know that moment when you’re at a party or a conference or whatever and you have no one to talk to, so you sidle up to a circle of people and then stand there awkwardly at the periphery, hoping for a chance to jump in? There is no more vulnerable position than this, to be teetering on the edge of personhood and oblivion, waiting to see whether a jury of your peers will decide that you exist.

My friend Wanda just doesn’t let that happen. If she’s in a circle and someone tries to join, she’ll go “Oh hey everybody this is Adam. Adam, we were just talking about...” and then we all go on normally. If she doesn’t know you, she’ll introduce herself quickly, tell you everybody’s names, and then pick up where the conversation left off.

This is the itsiest bitsiest mercy of all time, but when you’re on the receiving end of it, it feels like an angel has snatched you out of the maw of Hades. That’s why I call it the Circle of Hell Test: when you see someone writhing in social damnation, do you grab their hand, or do you let ‘em burn?

I think most people fail this test this because they’re too anxious about their own status, like “Hey man how can I affirm your personhood?? I’m still waiting to see if they affirm my personhood!” But this is the wrong way of looking at it. Bringing someone else into the fold doesn’t cost you status. It gives you status. Taking the floor and then handing it to someone else is a big conversational move, and you look cool when you do it. Wanda ends up seeming like the most high-status person in any conversation for exactly this reason.

3. THE GOTTMAN TEST #4

No one can convince my friend Micah of anything. He treats conversations like trench warfare—you have to send a full battalion to their deaths if you want to gain an inch of ground. When anybody tries to give him advice, he stares into the distance and waits for them to stop. Meanwhile, Micah is quick to tell other people how to live, and then he gets kinda huffy if you blow him off.

Oh, who am I kidding? Micah is me.

I’m usually skeptical of self-help books, but when I read that John Gottman’s Principle #4 for a Successful Marriage is “let your partner influence you,” I didn’t just feel seen. I felt caught. This is Gottman Test #4, and it applies not just to partners, but to people in general: do you expect to influence others, but refuse to be influenced yourself?

I think I’m so resistant to the idea of being swayed because I feel like I’m made out of opinions. Changing them would be like opening up my DNA and scrambling my nucleotides. That’s why I surround ‘em with barbed wire and mine fields and machine gunners. This assumes, of course, that I just happen to have all of my cytosines and guanines in exactly the right place, that none of my DNA is useless or mutated, and that every codon is critical—change one, and you change everything. I mean, if I admit my ranking of Bruce Springsteen albums is slightly out of order, then who am I anymore?

But it ain’t like that. Like genes, opinions acquire errors over time, and they have to be perpetually proofread and repaired, or else they start going wonky and you end up with a whole tumorous ideology. Unlike genes, however, those repairs generally have to come from outside. I always assume that it will feel frightening to let this happen, to reel in the barbed wire, to deactivate the mine field, to order the machine gunners to stand down. Instead, it feels like a relief to finally give up and agree that Born to Run is, in fact, superior to Born in the U.S.A.

4. THE CODEPENDENT PROBLEMS TEST

I recently walked through a train station that was plastered with ads like: “There’s a lot of stigma against disabilities, but we’re here to change that!” and “80% of Americans have a prejudice against people with disabilities. It’s time to lower that number!”

If you actually want to reduce prejudice toward people with disabilities, you would never ever run a campaign like that, not in a million years. When you tell everybody that there’s a lot of stigma against something, you stand a pretty good chance of increasing that stigma. Maybe the nonprofit that paid for these ads has a different theory of human behavior, or maybe the ads looked reasonable because that nonprofit cannot actually imagine a future without stigma. Perhaps because if that stigma went away, the nonprofit would have to go, too.2

I think of this as the Codependent Problems Test: do you actually want to solve your problem, or are you secretly depending on its continued existence? If you showed up to fight the dragon and found it already slain, would you be elated or disappointed?

After all, a righteous crusade gives you meaning and camaraderie, to the point where you can become addicted to the crusading itself. It is possible to form an entire identity around being mad at things, and to make those things grow by pouring your rage on them, which in turn gives you more things to be mad at. This is, in fact, the business model for approximately half the internet.

When I was an academic, I used to worry about getting scooped—if someone debuts my idea before I do, they get all the glory. As soon as I stopped publishing in journals and started blogging my research instead, this fear went away. I realized that I wasn’t actually looking for knowledge; I was looking for credit. I was in a codependent relationship with ignorance: I wanted it to keep existing until the exact moment that I, and only I, could make it go away.

5. THE MATCH YOUR FREAK TEST

Everybody loves my friends Tim and Renee because they are willing to match your freak. If you do something weird, they’ll do something weirder. Dance an embarrassing little jig, talk like you’re a courtier to Louis XIV, pretend you’re from a universe where 9/11 never happened, and they’ll be right there with you: “That’s so crazy! We’re from a universe where Saddam Hussein became a famous lifestyle TikTokker!”

Every moment you’re with another person, you are implicitly asking, “If I’m a little bit weird, will you be a little bit weird too?” And when you’re with Tim and Renee the answer is yes, yes, a thousand times yes. It’s hard to describe how good it feels when someone passes the Match Your Freak Test, to know that no matter how far you put yourself out there, you won’t be left hanging.

Technically this is called “Yes, And,” but in our attempt to mass-produce that idea, we’ve made it mechanical and cringe. (Somehow you don’t get the vibe right when you put people in a circle with coworkers they hate and force them all to play “Zip, Zap, Zop”.) I knew plenty of talented improvisers who would never disobey the letter of improv law, but would still find a way to make it clear that they hated your choices.

Matching someone’s freak isn’t about reluctantly agreeing to their reality. It’s about declining the opportunity to judge them, and choosing instead to do something that’s even more judge-able. It’s the opposite of being a bully—it’s seeing someone with a mustard stain on their shirt, and instead of pointing and laughing, you grab a bottle of mustard and squirt it all over yourself.

6. THE POINTLESS STATUS TEST

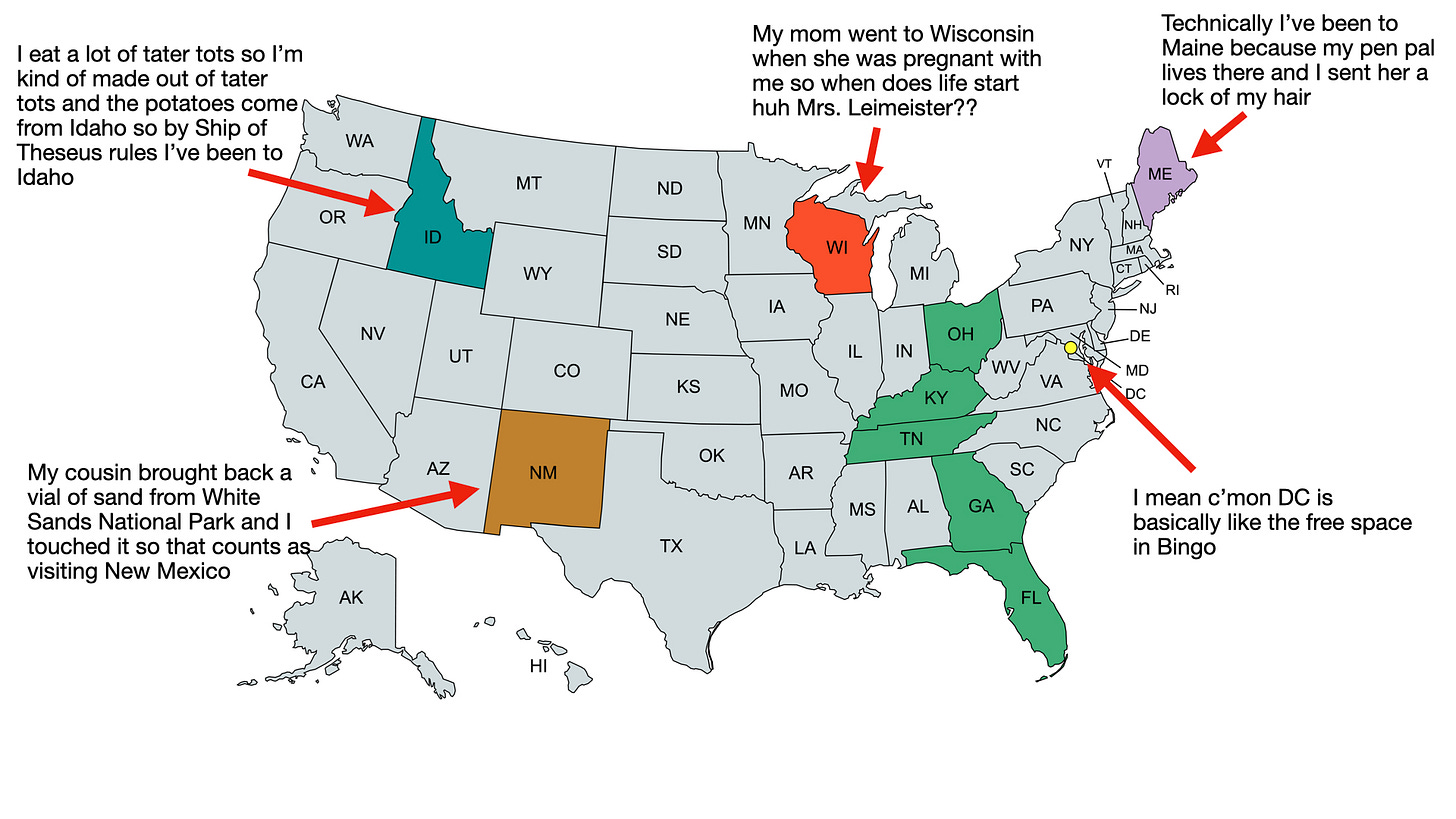

In fourth grade, the teacher handed us all a blank map of the US and told us to color in every state that we had visited. Immediately, my mission was clear: I needed to be the kid who had been to the most states. As I was sharpening my Crayolas, though, I saw this kid Ian coloring in swaths of the Northeast—as if, knowing this showdown would one day come, he had gone on a road trip through New England specifically to juice his stats with all those tiny states.

Desperate, I hatched a plan: I had once flown from Ohio to Florida to visit my uncle, so hadn’t I technically been “in” all of those intervening states? This led to a pitched metaphysical debate with the teacher, and many thought experiments later (“What if you drive through Pennsylvania but you never get out of the car?”, “What if you walk through Delaware on stilts, so that your feet don’t technically touch the ground?”), she relented and allowed me to identify all of my “flyover” states in a different color. That put me just barely ahead of Ian, who soon moved out of town, I assume because of his shame, or to up his numbers for our inevitable rematch.

That story has stuck in my head for decades because that stupid, petty instinct has never left me. I am constantly failing the Pointless Status Test—whenever there’s some way I could consider myself better than other people, no matter how stupid or arbitrary it is, I feel compelled to compete.

The problem isn’t the competition itself; it’s only a vice when it doesn’t produce anything useful. So I’m proud of my fourth-grade self for demonstrating creativity in the face of adversity. I just wish I had used it to do something other than win a status game that existed entirely inside my own head.

That’s why, in my opinion, we should feel the same derision toward people who engage in pointless competition as we feel toward people who embezzle public funds. We all benefit from the public goods that society provides—safety, trust, knowledge—and so we all owe society some portion of our efforts in return. If instead you squander your talents on the acquisition of purely positional goods, you are robbing the world of its due. It’s like commandeering a nuclear power plant so you can heat up a Hot Pocket.

7. THE TOO BUSY TO CARE TEST

In college, I crammed my schedule so full that my GCal was one solid block of red: classes, extracurriculars, jobs, committees, shows, research. My improv group would routinely rehearse from 11:15pm to 1:15am because that was literally the only time left. It felt like every dial of my life was permanently turned up to 11 and it was great.

Well, mostly great. One spring, Maya, a good friend of mine, was performing a play she had written for her senior thesis. A sacred rule among theater kids is that you go to each other’s shows—otherwise, you might have to perform your Vietnam era reimagining of The Music Man to no one. There was only one night I could possibly make it to Maya’s play, and when that night arrived I just...didn’t go. It wasn’t because I forgot. I decided. I wanted a few hours to finish an essay, to read, to respond to emails, to think, to sit motionless on my couch, and while I could have delayed all those things to some later time and nothing bad would have happened, I didn’t have the gumption to do it.

When Maya came by my room later that night, upset, and rightfully so, I realized for the first time: extreme busyness is a form of selfishness. When you’re running at 110% capacity, you’ve got nothing left for anybody else. Having slack in your life is prosocial, like carrying around spare change in your pocket in case someone needs it. My pockets were permanently empty—I was unable to bake anyone a birthday cake, proofread their essay, pick them up at the airport, or even, if I’m honest, think about them more than a few seconds. I was failing the Too Busy to Care Test. “Oh, you’re going through a breakup and need someone to talk to? No problem, just sign up for a 15-minute slot on my Calendly.”

I once read a study where they found that people’s perception of the care available to them was a better predictor of their mental health than the care they actually received. That made a lot of sense to me. It’s not every day that you need to call someone at 2am and bawl your eyes out. But every day you wonder: if I called, would someone pick up?

GIVING NOTICE

I’ve heard that assholes can occasionally transform into angels, but I’ve never seen it happen. Any improvement I’ve ever witnessed—in myself, in others, doesn’t matter—has been, to borrow Max Weber’s description of politics, “the strong and slow boring of hard boards.” That’s because there’s no switch in the mind marked “BE A BETTER PERSON”. Instead, becoming kinder and gentler is mainly the act of noticing—realizing that some small decision has moral weight, acting accordingly, and repeating that pattern over and over again.

It’s much easier, of course, to wait for a Road to Damascus moment, to put off any self-improvement to some dramatic day when the sky will open and God will reprimand you directly, so you can do all of your repenting and changing of ways at once. For me, anyway, that day is always permanently and conveniently located in the near future, so in the meantime I can enjoy my “Lord make me good, but not yet” phase.

If you accept that nothing is going to happen on the way to Damascus, to you or anyone else, if you let go of the myth of an imminent moral metamorphosis, you can instead enjoy a life lived under expectations that are both extremely consistent and extremely low. It is always possible to become a better person—even right this second!—but only a very very slightly better one. Whatever flaws you have today, you will probably have them tomorrow, and same goes for your loved ones. But you can shrink ‘em (your flaws, that is, not your loved ones) by the tiniest amount today, a bit more tomorrow, and a bit more after that.

It’s like you’re trying to move across the country, but each day, you can only move into the house that’s right next to yours. It might be months before you even make it to another zip code. But if you keep carrying your boxes from house to house, soon enough you’ll be on the other side of town, and then in the next state over, and then the next one after that. The most important thing to remember is: keep track of those states, because you never know when Ian might return.

In their earlier, more innocent days, they also brought us lolcats and rickrolling.

See also: the Shirky Principle.

I gave up those pointless status tests and feel so good about it when other people try to play me. Wait… did I just play the status game by claiming victory through opting out? 😂

With regard to the "Circle of Hell Test", what I like to share with students is the concept of the "Pac Man Circle". I picked this up from my friend Daniel Angerhausen of The Explainables (he's also an astrophysicist and expert on ML/AI). Basically, when you form a circle with other people to talk but there's a larger group around then you make your circle a Pac Man with a space that allows anyone else to feel welcomed into the circle. If someone takes that space, you introduce them or welcome them and the collectively make a new, larger Pac Man. I use this for the high school students on the trips I lead, and many of them love it.